From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This is one of a collection of articles which has a direct, or indirect relevance for the development of the UDP. Blogger Ref http://www.p2pfoundation.net/Universal_Debating_Project

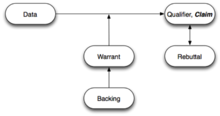

In informal logic and philosophy, an argument map is a visual representation of the structure of an argument. It includes the components of an argument such as a main contention, premises, co-premises, objections, rebuttals, and lemmas. Typically an argument map is a "box and arrow" diagram with boxes corresponding to propositions and arrows corresponding to relationships such as evidential support.

Argument maps are commonly used in the context of teaching and applying critical thinking.[1] The purpose of mapping is to uncover the logical structure of arguments, identify unstated assumptions, evaluate the support an argument offers for a conclusion, and aid understanding of debates. Argument maps are often designed to support deliberation of issues, ideas and arguments in wicked problems.

An argument map is not to be confused with a concept map or a mind map, which are less strict in relating claims.

Here is a more complex map. The objection 1A weakens the conclusion, while the reason 2A supports premise 1A-b of the objection:

Logical structure: Argument maps display an argument's logical structure more clearly than does the standard linear way of presenting arguments.

Critical thinking concepts: In learning to argument map, students master such key critical thinking concepts as "reason", "objection", "premise", "conclusion", "inference", "rebuttal", "unstated assumption", "co-premise", "strength of evidence", "logical structure", "independent evidence", etc. Mastering such concepts is not just a matter of memorizing their definitions or even being able to apply them correctly; it is also understanding why the distinctions these words mark are important and using that understanding to guide one's reasoning.

Visualization: Humans are highly visual and argument mapping may provide students with a basic set of visual schemas with which to understand argument structures.

More careful reading and listening: Learning to argument map teaches people to read and listen more carefully, and highlights for them the key questions "What is the logical structure of this argument?" and "How does this sentence fit into the larger structure?" In-depth cognitive processing is thus more likely.

More careful writing and speaking: Argument mapping helps people to state their reasoning and evidence more precisely, because the reasoning and evidence must fit explicitly into the map's logical structure.

Literal and intended meaning: Often, many statements in an argument do not precisely assert what the author meant. Learning to argument map enhances the complex skill of distinguishing literal from intended meaning.

Externalization: Writing something down and reviewing what one has written often helps reveal gaps and clarify one's thinking. Because the logical structure of argument maps is clearer than that of linear prose, the benefits of mapping will exceed those or ordinary writing.

Anticipating replies: Important to critical thinking is anticipating objections and considering the plausibility of different rebuttals. Mapping develops this anticipation skill, and so improves analysis.

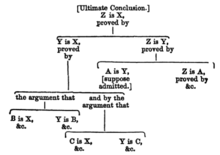

However, the technique did not become widely used, possibly because for complex arguments, it involved much writing and rewriting of the premises.

Legal philosopher and theorist John Henry Wigmore produced maps of legal arguments using numbered premises in the early 20th century,[4] based in part on the ideas of 19th century philosopher Henry Sidgwick who used lines to indicate relations between terms.[5]

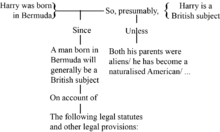

Stephen Toulmin, in a groundbreaking and influential book The Uses of Argument,[6] identified several elements to an argument which has been generalized. The Toulmin diagram is widely used in educational critical teaching.[7][8]

In 1998 a substantial series of maps released by Robert E. Horn stimulated widespread interest in the technique.[9] In 1999 articles in the journal New Scientist, Lingua Franca and the Philosophers' Magazine focused more attention on the project.[10]

Michael Scriven developed an argument diagram in 1976.[11]

In 1988, David Kelley proposed a structured diagram technique with numbered premises, and arrows indicating inferential relations.[12] The premises were to be listed at the side of the diagram for reference. The three forms here of an argument are serial, additive (or joint), and non-additive (or convergent), respectively. Kelley also had divergent arguments, where a single premise could act as a reason for multiple lines of argument. Kelley diagrams are also often shown as "ball and stick" diagrams.

In the 1990s, Tim van Gelder developed a series of computer applications that permitted the premises to be fully stated and edited in the diagram, rather than in a legend.[13][14] This also permitted reasons to be edited for clarity according to the principle of charity, whereby one reconstructs arguments so they are consistent with the best interpretation of authorial intentions. The first program, Reason!Able, was superseded by two subsequent programs, bCisive and Rationale. In 2011, Austhink Software sold the software rights to Kritisch Denken BV in the Netherlands.[14] Rationale permits reasons comprising one or more premises. This forces the arguer or analyst to identify the missing (unstated) premises based on the rule that there should be no danglers, that is, terms that only appear in one claim box of an argument (see Enthymeme). Here is a basic Rationale argument map:

Reasons consist of premises that support a final or intermediate conclusion. In this map, premises 2A-a and 2A-b support the intermediate conclusion 1A-a, which is a co-premise with 1A-b for the final conclusion.

Argument maps can also map objections to conclusions or premises:

In this map, objections are offered to premise 2A-b and also to the conclusion directly.

See the AIF original draft description (2006) and the full AIF-RDF ontology specifications in RDFS format.

Argument maps are commonly used in the context of teaching and applying critical thinking.[1] The purpose of mapping is to uncover the logical structure of arguments, identify unstated assumptions, evaluate the support an argument offers for a conclusion, and aid understanding of debates. Argument maps are often designed to support deliberation of issues, ideas and arguments in wicked problems.

An argument map is not to be confused with a concept map or a mind map, which are less strict in relating claims.

Contents

[hide]Introduction[edit]

This is a simple argument map. The conclusion is shown at the top, and the boxes linked to it represent supporting reasons, which comprise one or more premises. The reason, 1A, comprising two premises 1A-a and 1A-b, support the conclusion:Here is a more complex map. The objection 1A weakens the conclusion, while the reason 2A supports premise 1A-b of the objection:

Evidence that argument mapping improves critical thinking ability[edit]

There is empirical evidence that the skills developed in argument-mapping-based critical thinking courses substantially transfer to critical thinking done without argument maps. Alvarez's meta-analysis found that such critical thinking courses produced gains of around 0.70 SD, about twice as much as standard critical-thinking courses.[2] The tests used in the reviewed studies were standard critical-thinking tests.How argument mapping helps with critical thinking[edit]

The use of argument mapping has occurred within a number of disciplines, such as philosophy, management reporting, military and intelligence analysis, and public debates.Logical structure: Argument maps display an argument's logical structure more clearly than does the standard linear way of presenting arguments.

Critical thinking concepts: In learning to argument map, students master such key critical thinking concepts as "reason", "objection", "premise", "conclusion", "inference", "rebuttal", "unstated assumption", "co-premise", "strength of evidence", "logical structure", "independent evidence", etc. Mastering such concepts is not just a matter of memorizing their definitions or even being able to apply them correctly; it is also understanding why the distinctions these words mark are important and using that understanding to guide one's reasoning.

Visualization: Humans are highly visual and argument mapping may provide students with a basic set of visual schemas with which to understand argument structures.

More careful reading and listening: Learning to argument map teaches people to read and listen more carefully, and highlights for them the key questions "What is the logical structure of this argument?" and "How does this sentence fit into the larger structure?" In-depth cognitive processing is thus more likely.

More careful writing and speaking: Argument mapping helps people to state their reasoning and evidence more precisely, because the reasoning and evidence must fit explicitly into the map's logical structure.

Literal and intended meaning: Often, many statements in an argument do not precisely assert what the author meant. Learning to argument map enhances the complex skill of distinguishing literal from intended meaning.

Externalization: Writing something down and reviewing what one has written often helps reveal gaps and clarify one's thinking. Because the logical structure of argument maps is clearer than that of linear prose, the benefits of mapping will exceed those or ordinary writing.

Anticipating replies: Important to critical thinking is anticipating objections and considering the plausibility of different rebuttals. Mapping develops this anticipation skill, and so improves analysis.

History and current applications[edit]

History[edit]

The philosophical origins and tradition of argument mapping[edit]

In the Elements of Logic, which was published in 1826 and issued in many subsequent editions,[3] Archbishop Richard Whately gave probably the first form of an argument map, introducing it with the suggestion that "many students probably will find it a very clear and convenient mode of exhibiting the logical analysis of the course of argument, to draw it out in the form of a Tree, or Logical Division".However, the technique did not become widely used, possibly because for complex arguments, it involved much writing and rewriting of the premises.

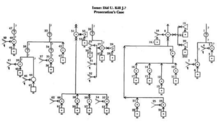

Legal philosopher and theorist John Henry Wigmore produced maps of legal arguments using numbered premises in the early 20th century,[4] based in part on the ideas of 19th century philosopher Henry Sidgwick who used lines to indicate relations between terms.[5]

Stephen Toulmin, in a groundbreaking and influential book The Uses of Argument,[6] identified several elements to an argument which has been generalized. The Toulmin diagram is widely used in educational critical teaching.[7][8]

In 1998 a substantial series of maps released by Robert E. Horn stimulated widespread interest in the technique.[9] In 1999 articles in the journal New Scientist, Lingua Franca and the Philosophers' Magazine focused more attention on the project.[10]

Anglophone argument diagramming in the 20th century[edit]

Dealing with the failure of formal reduction of informal argumentation, English speaking argumentation theory developed diagrammatic approaches to informal reasoning over a period of fifty years.Michael Scriven developed an argument diagram in 1976.[11]

Reasons consist of premises that support a final or intermediate conclusion. In this map, premises 2A-a and 2A-b support the intermediate conclusion 1A-a, which is a co-premise with 1A-b for the final conclusion.

Argument maps can also map objections to conclusions or premises:

In this map, objections are offered to premise 2A-b and also to the conclusion directly.

Difficulties with the philosophical tradition[edit]

It has traditionally been hard to separate teaching critical thinking from the philosophical tradition of teaching logic and method, and most critical thinking textbooks have been written by philosophers. Informal logic textbooks are replete with philosophical examples, but it is unclear whether the approach in such textbooks transfers to non-philosophy students.[7] There appears to be little statistical effect after such classes. Argument mapping, however, has a measurable effect according to many studies.[15] For example, instruction in argument mapping has been shown to improve the critical thinking skills of business students.[16]Applications[edit]

Argument maps have been applied in many areas, but foremost in educational, academic and business settings.[17] It has also been proposed that argument mapping has a great potential to improve how we understand and execute democracy, in reference to the ongoing evolution of e-democracy.[18]Standards[edit]

Argument Interchange Format[edit]

The Argument Interchange Format, AIF, is an international effort to develop a representational mechanism for exchanging argument resources between research groups, tools, and domains using a semantically rich language. AIF-RDF, is the extended ontology represented in the Resource Description Framework Schema (RDFS) semantic language. Though AIF is still something of a moving target, it is settling down.[19]See the AIF original draft description (2006) and the full AIF-RDF ontology specifications in RDFS format.

Legal Knowledge Interchange Format[edit]

The Legal Knowledge Interchange Format (LKIF), developed in the European ESTRELLA project, is an XML schema for rules and arguments, designed with the goal of becoming a standard for representing and interchanging policy, legislation and cases, including their justificatory arguments, in the legal domain. LKIF builds on and uses the Web Ontology Language (OWL) for representing concepts and includes a reusable basic ontology of legal concepts.See also[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Argument maps. |

- Araucaria (software)

- Argumentation theory

- Compendium (software)

- Concept map

- Debategraph

- Flow (policy debate)

- Informal fallacy

- Information graphics

- Logic

- Mind map

Notes[edit]

- Jump up ^ For example: Facione 2013, p. 86; Fisher 2004; Kelley 2014, p. 73; Walton 2013, p. 10

- Jump up ^ Álvarez Ortiz 2007, pp. 69–70 et seq

- Jump up ^ Whately 1834 (first published 1826)

- Jump up ^ Wigmore 1913

- Jump up ^ Goodwin 2000

- Jump up ^ Toulmin 2003 (first published 1958)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Simon, Erduran & Osborne 2006

- Jump up ^ Böttcher & Meisert 2011; Macagno & Konstantinidou 2013

- Jump up ^ Horn 1998 and Robert E. Horn, "Infrastructure for navigating interdisciplinary debates: critical decisions for representing argumentation", in Kirschner, Buckingham Shum & Carr 2003, p. 165–184

- Jump up ^ Holmes 1999

- Jump up ^ Scriven 1976

- Jump up ^ Kelley 1988

- Jump up ^ van Gelder 2007

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berg et al. 2009

- Jump up ^ Twardy 2004; Álvarez Ortiz 2007; Harrell 2008; Yanna Rider and Neil Thomason, "Cognitive and pedagogical benefits of argument mapping: LAMP guides the way to better thinking", in Okada, Buckingham Shum & Sherborne 2008, p. 113–130; Dwyer 2011; Davies 2012

- Jump up ^ Carrington et al. 2011; Kunsch, Schnarr & van Tyle 2014

- Jump up ^ Kirschner, Buckingham Shum & Carr 2003; Okada, Buckingham Shum & Sherborne 2008

- Jump up ^ Hilbert 2009

- Jump up ^ Bex et al. 2013

References[edit]

- Álvarez Ortiz, Claudia María (2007). Does philosophy improve critical thinking skills? (PDF) (M.A.). Department of Philosophy, University of Melbourne. OCLC 271475715.

- Berg, Timo ter; van Gelder, Tim; Patterson, Fiona; Teppema, Sytske (2009). Critical thinking: reasoning and communicating with Rationale. Amsterdam: Pearson Education Benelux. ISBN 9043018015. OCLC 301884530.

- Bex, Floris; Modgil, Sanjay; Prakken, Henry; Reed, Chris (2013). "On logical specifications of the Argument Interchange Format" (PDF). Journal of Logic and Computation 23 (5): 951–989. doi:10.1093/logcom/exs033.

- Böttcher, Florian; Meisert, Anke (February 2011). "Argumentation in science education: a model-based framework". Science & Education 20 (2): 103–140. doi:10.1007/s11191-010-9304-5.

- Carrington, Michal; Chen, Richard; Davies, Martin; Kaur, Jagjit; Neville, Benjamin (June 2011). "The effectiveness of a single intervention of computer‐aided argument mapping in a marketing and a financial accounting subject" (PDF). Higher Education Research & Development 30 (3): 387–403. doi:10.1080/07294360.2011.559197.

- Davies, Martin (Summer 2012). "Computer-aided argument mapping as a tool for teaching critical thinking". International Journal of Learning and Media 4 (3-4): 79–84. doi:10.1162/IJLM_a_00106.

- Dwyer, Christopher Peter (2011). The evaluation of argument mapping as a learning tool (PDF) (Ph.D.). School of Psychology, National University of Ireland, Galway. OCLC 812818648.

- Facione, Peter A. (2013) [2011]. THINK critically (2nd ed.). Boston: Pearson. ISBN 0205490980. OCLC 770694200.

- Fisher, Alec (2004) [1988]. The logic of real arguments (2nd ed.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511818455. ISBN 0521654815. OCLC 54400059.

- van Gelder, Tim (2007). "The rationale for Rationale" (PDF). Law, Probability and Risk 6 (1-4): 23–42. doi:10.1093/lpr/mgm032.

- Goodwin, Jean (2000). "Wigmore's chart method". Informal Logic 20 (3): 223–243.

- Harrell, Maralee (December 2008). "No computer program required: even pencil-and-paper argument mapping improves critical-thinking skills" (PDF). Teaching Philosophy 31 (4): 351–374. doi:10.5840/teachphil200831437.

- Hilbert, Martin (April 2009). "The maturing concept of e-democracy: from e-voting and online consultations to democratic value out of jumbled online chatter" (PDF). Journal of Information Technology and Politics 6 (2): 87–110. doi:10.1080/19331680802715242.

- Holmes, Bob (10 July 1999). "Beyond words". New Scientist (2194).

- Horn, Robert E. (1998). Visual language: global communication for the 21st century. Bainbridge Island, WA: MacroVU, Inc. ISBN 189263709X. OCLC 41138655.

- Kelley, David (1988). The art of reasoning (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393959139. OCLC 16984878.

- Kelley, David (2014) [1988]. The art of reasoning: an introduction to logic and critical thinking (4th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393930785. OCLC 849801096.

- Kirschner, Paul Arthur; Buckingham Shum, Simon J; Carr, Chad S, eds. (2003). Visualizing argumentation: software tools for collaborative and educational sense-making. Computer supported cooperative work. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-0037-9. ISBN 1852336641. OCLC 50676911.

- Kunsch, David W.; Schnarr, Karin; van Tyle, Russell (November 2014). "The use of argument mapping to enhance critical thinking skills in business education". Journal of Education for Business 89 (8): 403–410. doi:10.1080/08832323.2014.925416.

- Macagno, Fabrizio; Konstantinidou, Aikaterini (August 2013). "What students' arguments can tell us: using argumentation schemes in science education". Argumentation 27 (3): 225–243. doi:10.1007/s10503-012-9284-5.

- Okada, Alexandra; Buckingham Shum, Simon J; Sherborne, Tony, eds. (2008). Knowledge cartography: software tools and mapping techniques. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-84800-149-7. ISBN 9781848001480. OCLC 195735592.

- Scriven, Michael (1976). Reasoning. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070558825. OCLC 2800373.

- Simon, Shirley; Erduran, Sibel; Osborne, Jonathan (2006). "Learning to teach argumentation: research and development in the science classroom" (PDF). International Journal of Science Education 28 (2-3): 235–260. doi:10.1080/09500690500336957.

- Toulmin, Stephen E. (2003) [1958]. The uses of argument (Updated ed.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511840005. ISBN 0521534836. OCLC 57253830.

- Twardy, Charles R. (June 2004). "Argument maps improve critical thinking" (PDF). Teaching Philosophy 27 (2): 95–116. doi:10.5840/teachphil200427213.

- Walton, Douglas N. (2013). Methods of argumentation. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139600187. ISBN 1107677335. OCLC 830523850.

- Whately, Richard (1834) [1826]. Elements of logic: comprising the substance of the article in the Encyclopædia metropolitana: with additions, &c. (5th ed.). London: B. Fellowes. OCLC 1739330.

- Wigmore, John Henry (1913). The principles of judicial proof: as given by logic, psychology, and general experience, and illustrated in judicial trials. Boston: Little Brown. OCLC 1938596.

Further reading[edit]

- Facione, Peter A.; Facione, Noreen C. (2007). Thinking and reasoning in human decision making: the method of argument and heuristic analysis. Milbrae, CA: California Academic Press. ISBN 1891557580. OCLC 182039452.

- Freeman, James B. (1991). Dialectics and the macrostructure of arguments: a theory of argument structure. Berlin; New York: Foris Publications. ISBN 3110133903. OCLC 24429943.

- van Gelder, Tim (17 February 2009). "What is argument mapping?". timvangelder.com. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- Harrell, Maralee (June 2005). "Using argument diagramming software in the classroom" (PDF). Teaching Philosophy 28 (2): 163–177. doi:10.5840/teachphil200528222.

- Reed, Chris; Rowe, Glenn (2007). "A pluralist approach to argument diagramming". Law, Probability and Risk 6 (1-4): 59–85. doi:10.1093/lpr/mgm030.

- Reed, Chris; Rowe, Glenn; Walton, Douglas; Macagno, Fabrizio (March 2007). "Argument diagramming in logic, law and artificial intelligence" (PDF). The Knowledge Engineering Review 22 (1): 87–109. doi:10.1017/S0269888907001051.

- Scheuer, Oliver; Loll, Frank; Pinkwart, Niels; McLaren, Bruce M. (2010). "Computer-supported argumentation: a review of the state of the art" (PDF). International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 5 (1): 43–102. doi:10.1007/s11412-009-9080-x.

- Verheij, Bart (2005). Virtual arguments: on the design of argument assistants for lawyers and other arguers. Information technology & law series 6. The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press. ISBN 9789067041904. OCLC 59617214.

External links[edit]

Argument mapping software[edit]

- Araucaria (open source, cross platform/Java)

- Argumentative (open source, Windows); supports single-user, graphical argumentation

- bCisive (commercial, Windows); supports reasoning and decision making by mapping decision problems, options and arguments.

- Compendium (open source, cross platform/Java)

- DeMMaTTouL [in Spanish] (open source, Linux, Windows, Mac); argument mapping using the Toulmin Model, export to HTML (Download from Sourceforge)

- PIRIKA (PIlot for the RIght Knowledge and Argument) (open source, Linux, Windows)

- PIRIKA on iPad (open source)

Online, collaborative software[edit]

- Arguman.org (user interface in Turkish, discuss arguments, opensource project)

- AGORA-net (user interface in English, German, Spanish, and Russian)

- Argunet

- bCisiveOnline

- Carneades (open source, argument (re)construction, evaluation, mapping and interchange)

- Collam (JavaScript library for visualizing argument maps)

- CrystalTower (open debate map built on syllogisms/arguments)

- Debategraph

- DebateWithMe (Premise-Premise-Conclusion structure based maps)

- Deliberatorium (MIT)

- Rationale Online

- Riyarchy (Collaborative argument map for outlining and ending debates)

- Theorymaps (a causal & theory mapping tool designed specifically to map out arguments presented in an empirical research article)

- TruthMapping

Academic[edit]

- ArgDF (a Semantic Web-based argumentation system)

- Argumap Yahoo Group

- Argument & Computation research journal

- Argument Mapping in Your Subject (resource site for college-level educators integrating argument mapping into their teaching)

- Scholarly Ontologies Project

Conferences[edit]

- IJCAI International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence

- AISB Society for the Study of Artificial Intelligence and Simulation of Behaviour

- Argumentation in Multi-Agent Systems (ArgMAS) Workshop Series

- CMNA Computational Models of Natural Argument

- COMMA Computational Models of Argument

- ISSA International Society for the Study of Argumentation

No comments:

Post a Comment