The trolley problem is a thought experiment in ethics. The general form of the problem is this:

Beginning in 2001, the trolley problem and its variants have been used extensively in empirical research on moral psychology. Trolley problems have also been a topic of popular books.[9] The problem often arises in the discussion of the ethics of the design of autonomous vehicles.

The initial trolley problem also supports comparison to other, related, dilemmas:

One clear distinction is that in the first case, one does not intend harm towards anyone – harming the one is just a side effect of switching the trolley away from the five. However, in the second case, harming the one is an integral part of the plan to save the five. This is an argument Shelly Kagan considers and ultimately rejects, in The Limits of Morality.[12]

A claim can be made that the difference between the two cases is that in the second, you intend someone's death to save the five, and this is wrong, whereas, in the first, you have no such intention. This solution is essentially an application of the doctrine of double effect, which says that you may take action which has bad side effects, but deliberately intending harm (even for good causes) is wrong.

There is also the uncertainty that your non-action would have led to the death of the five people, as e.g. the trolley might have suffered an engine breakdown before hitting the five. On the other hand, if you throw the fat man on the rails, it is certain that you killed him, whereas it is not certain that you needed to kill him to save the lives of the five.

Act utilitarians deny this. Peter Unger (a non-utilitarian) rejects that it can make a substantive moral difference whether you bring the harm to the one or whether you move the one into the path of the harm.[13] Note, however, that rule utilitarians do not have to accept this and can say that pushing the fat man over the bridge violates a rule to which adherence is necessary for bringing about the greatest happiness for the greatest number.[14]

Another distinction is that the first case is similar to a pilot in an airplane that has lost power and is about to crash and currently heading towards a heavily populated area. Even if he knows for sure that innocent people will die if he redirects the plane to a less populated area – people who are "uninvolved" – he will actively turn the plane without hesitation. It may well be considered noble to sacrifice your own life to protect others, but morally or legally allowing murder of an innocent person in order to save five people may be insufficient justification.[clarification needed]

The rejoining variant may not be fatal to the "using a person as a means" argument. This has been suggested by Michael J. Costa in his 1987 article "Another Trip on the Trolley", where he points out that if we fail to act in this scenario we will effectively be allowing the five to become a means to save the one. If we do nothing, then the impact of the trolley into the five will slow it down and prevent it from circling around and killing the one.[citation needed] As in either case, some will become a means to saving others, then we are permitted to count the numbers. This approach requires that we downplay the moral difference between doing and allowing.

However, this line of reasoning is no longer applicable if a slight change is made to the track arrangements such that the one person was never in danger to begin with, even if the 5 people had been absent – or even with no track changes, if a change is made such that the one person is high on the gradient while the five are low, so that the trolley cannot reach the one. The question has therefore not been answered. It is also possible to change the points to "1A, 2B", causing the trolley to continue straight ahead towards the 5, avoiding the 1, but then be derailed on purpose where the loop rejoins the main track, before reaching the 5, killing no-one.

Unger therefore argues that different responses to these sorts of problems are based more on psychology than ethics – in this new case, he says, the only important difference is that the man in the yard does not seem particularly "involved". Unger claims that people therefore believe the man is not "fair game", but says that this lack of involvement in the scenario cannot make a moral difference.

Unger also considers cases which are more complex than the original trolley problem, involving more than just two results. In one such case, it is possible to do something which will (a) save the five and kill four (passengers of one or more trolleys and/or the hammock-sleeper), (b) save the five and kill three, (c) save the five and kill two, (d) save the five and kill one, or (e) do nothing and let five die.

A 2009 survey published in a 2013 paper by David Bourget and David Chalmers shows that 68% of professional philosophers would switch (sacrifice the one individual to save five lives) in the case of the trolley problem, 8% would not switch, and the remaining 24% had another view or could not answer.[25]

The 2015 film Eye in the Sky uses a variant of this ethical dilemma,[36] when characters are forced to decide whether to deliver a pre-emptive drone strike against two suicide bombers, in a situation where the attack would also kill a young child selling bread near the proposed strike point. The tension mounts as all the people required to make the decision on acceptable collateral damage weigh in.

A reference to the trolley problem is made in the 2014 film The Fault In Our Stars, by the character Peter Van Houten to Hazel Grace Lancaster at a funeral. Previously, Van Houten has used references to various mathematical conundrums and thought problems in obtuse efforts to explain the reality of "unfair" death from cancer. Due to earlier hurts and insults imposed by Van Houten, Lancaster dismisses him without allowing an explanation for the reference and the viewer is left to infer the meaning.

A cartoon illustration of the problem, drawn by Jesse Prinz, has attained cult status as a meme, with the image being edited in various ways to illustrate variations on the trolley problem, both as serious ethical debating points and as humorous parodies, often involving references to topical issues, other philosophical problems and other memes. Know Your Meme claims that the memes originated on 4chan around 2013,[37] and have since spread across the internet.

The problem is referenced in two episodes of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt.

The trolley problem makes an appearance in the opening of the video game Prey (2017), where the player must give their decision in order to proceed through the opening of the game.

A Facebook page under the name "Trolley Problem Memes" was recognized for its popularity on Facebook.[38] The group administration commonly shares comical variations of the trolley problem and often mixes in multiple types of philosophical dilemmas.[39] A common joke among the users regards "multi-track drifting" in which the lever is pulled after the first set of wheels pass the track thereby creating a third, often humorous, solution.[40]

The Trolley Problem is also mentioned in season 5 episode 8, "Tied to the Tracks," of Orange Is the New Black.

The Trolley Problem is discussed in 2 episodes of the Radiolab Podcast by WNYCStudios.

The video game Life Is Strange uses a variant of the trolley problem. At the end of the game, the protagonist Max has to make a choice whether to turn back time. Changing time will kill her best friend/girlfriend Chloe but save the Arcadia Bay. On the other hand not changing time will mean that Chloe will be safe but everyone in the Arcadia Bay will die. The player can choose whether to save Chloe or Arcadia Bay, which leads to two different alternative ends.

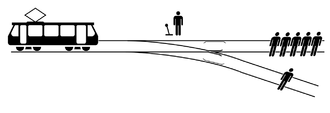

There is a runaway trolley barreling down the railway tracks. Ahead, on the tracks, there are five people tied up and unable to move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, you notice that there is one person on the side track. You have two options:The modern form of the problem was first introduced by Philippa Foot in 1967,[1] but also extensively analysed by Judith Thomson,[2][3] Frances Kamm,[4] and Peter Unger.[5] However an earlier version, in which the one person to be sacrificed on the track was the switchman's child, was part of a moral questionnaire given to undergraduates at the University of Wisconsin in 1905,[6][7] and the German legal scholar Hans Welzel discussed a similar problem in 1951.[8]

Which is the most ethical choice?

- Do nothing, and the trolley kills the five people on the main track.

- Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track where it will kill one person.

Beginning in 2001, the trolley problem and its variants have been used extensively in empirical research on moral psychology. Trolley problems have also been a topic of popular books.[9] The problem often arises in the discussion of the ethics of the design of autonomous vehicles.

Contents

[hide]Original dilemma[edit]

Foot's original structure of the problem ran as follows:Suppose that a judge or magistrate is faced with rioters demanding that a culprit be found for a certain crime and threatening otherwise to take their own bloody revenge on a particular section of the community. The real culprit being unknown, the judge sees himself as able to prevent the bloodshed only by framing some innocent person and having him executed. Beside this example is placed another in which a pilot whose airplane is about to crash is deciding whether to steer from a more to a less inhabited area. To make the parallel as close as possible it may rather be supposed that he is the driver of a runaway tram which he can only steer from one narrow track on to another; five men are working on one track and one man on the other; anyone on the track he enters is bound to be killed. In the case of the riots the mob have five hostages, so that in both examples the exchange is supposed to be one man's life for the lives of five.[1]A utilitarian view asserts that it is obligatory to steer to the track with one man on it. According to classical utilitarianism, such a decision would be not only permissible, but, morally speaking, the better option (the other option being no action at all).[10] An alternate viewpoint is that since moral wrongs are already in place in the situation, moving to another track constitutes a participation in the moral wrong, making one partially responsible for the death when otherwise no one would be responsible. An opponent of action may also point to the incommensurability of human lives. Under some interpretations of moral obligation, simply being present in this situation and being able to influence its outcome constitutes an obligation to participate. If this is the case, then deciding to do nothing would be considered an immoral act if one values five lives more than one.

Related problems[edit]

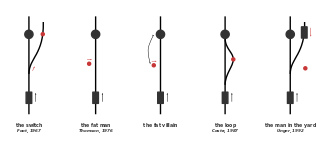

The fat man[edit]

One such is that offered by Judith Jarvis Thomson:As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by putting something very heavy in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you – your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?Resistance to this course of action seems strong; when asked, a majority of people will approve of pulling the switch to save a net of four lives, but will disapprove of pushing the fat man to save a net of four lives.[11] This has led to attempts to find a relevant moral distinction between the two cases.

One clear distinction is that in the first case, one does not intend harm towards anyone – harming the one is just a side effect of switching the trolley away from the five. However, in the second case, harming the one is an integral part of the plan to save the five. This is an argument Shelly Kagan considers and ultimately rejects, in The Limits of Morality.[12]

A claim can be made that the difference between the two cases is that in the second, you intend someone's death to save the five, and this is wrong, whereas, in the first, you have no such intention. This solution is essentially an application of the doctrine of double effect, which says that you may take action which has bad side effects, but deliberately intending harm (even for good causes) is wrong.

There is also the uncertainty that your non-action would have led to the death of the five people, as e.g. the trolley might have suffered an engine breakdown before hitting the five. On the other hand, if you throw the fat man on the rails, it is certain that you killed him, whereas it is not certain that you needed to kill him to save the lives of the five.

Act utilitarians deny this. Peter Unger (a non-utilitarian) rejects that it can make a substantive moral difference whether you bring the harm to the one or whether you move the one into the path of the harm.[13] Note, however, that rule utilitarians do not have to accept this and can say that pushing the fat man over the bridge violates a rule to which adherence is necessary for bringing about the greatest happiness for the greatest number.[14]

Another distinction is that the first case is similar to a pilot in an airplane that has lost power and is about to crash and currently heading towards a heavily populated area. Even if he knows for sure that innocent people will die if he redirects the plane to a less populated area – people who are "uninvolved" – he will actively turn the plane without hesitation. It may well be considered noble to sacrifice your own life to protect others, but morally or legally allowing murder of an innocent person in order to save five people may be insufficient justification.[clarification needed]

The fat villain[edit]

The further development of this example involves the case, where the fat man is, in fact, the villain who put these five people in peril. In this instance, pushing the villain to his death, especially to save five innocent people, seems not only morally justifiable but perhaps even imperative.[15] This is essentially related to another thought experiment, known as ticking time bomb scenario, which forces one to choose between two morally questionable acts.The loop variant[edit]

The claim that it is wrong to use the death of one to save five runs into a problem with variants like this:As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. As in the first case, you can divert it onto a separate track. However, this diversion loops back around to rejoin the main track, so diverting the trolley still leaves it on a path to run over the five people. But, on this track is a single fat person who, when he is killed by the trolley, will stop it from continuing on to the five people. Should you flip the switch?The only difference between this case and the original trolley problem is that an extra piece of track has been added, which seems a trivial difference (especially since the trolley won't travel down it anyway). So, if we originally decided that it is permissible or necessary to flip the switch, intuition may suggest that the answer should not have changed. However, in this case, the death of the one actually is part of the plan to save the five.

The rejoining variant may not be fatal to the "using a person as a means" argument. This has been suggested by Michael J. Costa in his 1987 article "Another Trip on the Trolley", where he points out that if we fail to act in this scenario we will effectively be allowing the five to become a means to save the one. If we do nothing, then the impact of the trolley into the five will slow it down and prevent it from circling around and killing the one.[citation needed] As in either case, some will become a means to saving others, then we are permitted to count the numbers. This approach requires that we downplay the moral difference between doing and allowing.

However, this line of reasoning is no longer applicable if a slight change is made to the track arrangements such that the one person was never in danger to begin with, even if the 5 people had been absent – or even with no track changes, if a change is made such that the one person is high on the gradient while the five are low, so that the trolley cannot reach the one. The question has therefore not been answered. It is also possible to change the points to "1A, 2B", causing the trolley to continue straight ahead towards the 5, avoiding the 1, but then be derailed on purpose where the loop rejoins the main track, before reaching the 5, killing no-one.

Transplant[edit]

Here is an alternative case, due to Judith Jarvis Thomson,[3] containing similar numbers and results, but without a trolley:A brilliant transplant surgeon has five patients, each in need of a different organ, each of whom will die without that organ. Unfortunately, there are no organs available to perform any of these five transplant operations. A healthy young traveler, just passing through the city the doctor works in, comes in for a routine checkup. In the course of doing the checkup, the doctor discovers that his organs are compatible with all five of his dying patients. Suppose further that if the young man were to disappear, no one would suspect the doctor. Do you support the morality of the doctor to kill that tourist and provide his healthy organs to those five dying persons and save their lives?

The man in the yard[edit]

Unger argues extensively against traditional non-utilitarian responses to trolley problems. This is one of his examples:As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You can divert its path by colliding another trolley into it, but if you do, both will be derailed and go down a hill, and into a yard where a man is sleeping in a hammock. He would be killed. Should you proceed?Responses to this are partly dependent on whether the reader has already encountered the standard trolley problem (since there is a desire to keep one's responses consistent), but Unger notes that people who have not encountered such problems before are quite likely to say that, in this case, the proposed action would be wrong.

Unger therefore argues that different responses to these sorts of problems are based more on psychology than ethics – in this new case, he says, the only important difference is that the man in the yard does not seem particularly "involved". Unger claims that people therefore believe the man is not "fair game", but says that this lack of involvement in the scenario cannot make a moral difference.

Unger also considers cases which are more complex than the original trolley problem, involving more than just two results. In one such case, it is possible to do something which will (a) save the five and kill four (passengers of one or more trolleys and/or the hammock-sleeper), (b) save the five and kill three, (c) save the five and kill two, (d) save the five and kill one, or (e) do nothing and let five die.

Empirical research[edit]

In 2001, Joshua Greene and colleagues published the results of the first significant empirical investigation of people's responses to trolley problems.[16] Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, they demonstrated that "personal" dilemmas (like pushing a man off a footbridge) preferentially engage brain regions associated with emotion, whereas "impersonal" dilemmas (like diverting the trolley by flipping a switch) preferentially engaged regions associated with controlled reasoning. On these grounds, they advocate for the dual-process account of moral decision-making. Since then, numerous other studies have employed trolley problems to study moral judgment, investigating topics like the role and influence of stress,[17] emotional state,[18] different types of brain damage,[19] physiological arousal,[20] different neurotransmitters,[21] and genetic factors[22] on responses to trolley dilemmas.Survey data[edit]

The trolley problem has been the subject of many surveys in which approximately 90% of respondents have chosen to kill the one and save the five. [23] If the situation is modified where the one sacrificed for the five was a relative or romantic partner, respondents are much less likely to be willing to sacrifice their life.[24]A 2009 survey published in a 2013 paper by David Bourget and David Chalmers shows that 68% of professional philosophers would switch (sacrifice the one individual to save five lives) in the case of the trolley problem, 8% would not switch, and the remaining 24% had another view or could not answer.[25]

Implications for autonomous vehicles[edit]

Problems analogous to the trolley problem arise in the design of autonomous cars, in situations where the car's software is forced during a potential crash scenario to choose between multiple courses of action (sometimes including options which include the death of the car's occupants), all of which may cause harm.[26][27][28][29][30] A platform called Moral Machine[31] was created by MIT Media Lab to allow the public to express their opinions on what decisions autonomous vehicles should make in scenarios that use the trolley problem paradigm. Other approaches make use of virtual reality to assess human behavior in experimental settings.[32][33]In popular culture[edit]

In an urban legend that has existed since at least the mid-1960s, the decision must be made by a drawbridge keeper who must choose between sacrificing a passenger train or his own four-year-old son.[34] There is a 2003 Czech short film titled Most ["Bridge" in English] and The Bridge (USA) which deals with a similar plot.[35] This version is often given as an illustration of the Christian belief that God sacrificed his son, Jesus Christ.[34]The 2015 film Eye in the Sky uses a variant of this ethical dilemma,[36] when characters are forced to decide whether to deliver a pre-emptive drone strike against two suicide bombers, in a situation where the attack would also kill a young child selling bread near the proposed strike point. The tension mounts as all the people required to make the decision on acceptable collateral damage weigh in.

A reference to the trolley problem is made in the 2014 film The Fault In Our Stars, by the character Peter Van Houten to Hazel Grace Lancaster at a funeral. Previously, Van Houten has used references to various mathematical conundrums and thought problems in obtuse efforts to explain the reality of "unfair" death from cancer. Due to earlier hurts and insults imposed by Van Houten, Lancaster dismisses him without allowing an explanation for the reference and the viewer is left to infer the meaning.

A cartoon illustration of the problem, drawn by Jesse Prinz, has attained cult status as a meme, with the image being edited in various ways to illustrate variations on the trolley problem, both as serious ethical debating points and as humorous parodies, often involving references to topical issues, other philosophical problems and other memes. Know Your Meme claims that the memes originated on 4chan around 2013,[37] and have since spread across the internet.

The problem is referenced in two episodes of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt.

The trolley problem makes an appearance in the opening of the video game Prey (2017), where the player must give their decision in order to proceed through the opening of the game.

A Facebook page under the name "Trolley Problem Memes" was recognized for its popularity on Facebook.[38] The group administration commonly shares comical variations of the trolley problem and often mixes in multiple types of philosophical dilemmas.[39] A common joke among the users regards "multi-track drifting" in which the lever is pulled after the first set of wheels pass the track thereby creating a third, often humorous, solution.[40]

The Trolley Problem is also mentioned in season 5 episode 8, "Tied to the Tracks," of Orange Is the New Black.

The Trolley Problem is discussed in 2 episodes of the Radiolab Podcast by WNYCStudios.

The video game Life Is Strange uses a variant of the trolley problem. At the end of the game, the protagonist Max has to make a choice whether to turn back time. Changing time will kill her best friend/girlfriend Chloe but save the Arcadia Bay. On the other hand not changing time will mean that Chloe will be safe but everyone in the Arcadia Bay will die. The player can choose whether to save Chloe or Arcadia Bay, which leads to two different alternative ends.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Philippa Foot, The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect in Virtues and Vices (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1978) (originally appeared in the Oxford Review, Number 5, 1967.)

- Jump up ^ Judith Jarvis Thomson, Killing, Letting Die, and the Trolley Problem, 59 The Monist 204-17 (1976)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Judith Jarvis Thomson, The Trolley Problem, 94 Yale Law Journal 1395–1415 (1985)

- Jump up ^ Francis Myrna Kamm, Harming Some to Save Others, 57 Philosophical Studies 227-60 (1989)

- Jump up ^ Peter Unger, Living High and Letting Die (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996)

- Jump up ^ Frank Chapman Sharp, A Study of the Influence of Custom on the Moral Judgment Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin no.236 (Madison, June 1908), 138.

- Jump up ^ Frank Chapman Sharp, Ethics (New York: The Century Co, 1928), 42-44, 122.

- Jump up ^ Hans Welzel, ZStW Zeitschrift für die gesamte Strafrechtswissenschaft 63 [1951], 47ff.

- Jump up ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/24/books/review/would-you-kill-the-fat-man-and-the-trolley-problem.html?_r=0

- Jump up ^ Barcalow, Emmett, Moral Philosophy: Theories and Issues. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2007. Print.

- Jump up ^ Peter Singer, Ethics and Intuitions The Journal of Ethics (2005). http://www.utilitarian.net/singer/by/200510--.pdf

- Jump up ^ Shelly Kagan, The Limits of Morality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989)[clarify this, please]

- Jump up ^ Unger, Peter. "Causing and Preventing Serious Harm." Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition 65(1992):227–255

- Jump up ^ Mizrahi, Moti (2012-05-04). "Think: Just Do It!: [PL 431] Trolley Problem and rule-utilitarianism". Think. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- Jump up ^ Carneades.org (2013-10-07), The Fat Villain Trolley Problem (90 Second Philosophy), retrieved 2016-09-04

- Jump up ^ Greene, Joshua D.; Sommerville, R. Brian; Nystrom, Leigh E.; Darley, John M.; Cohen, Jonathan D. (2001-09-14). "An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment". Science. 293 (5537): 2105–2108. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11557895. doi:10.1126/science.1062872.

- Jump up ^ Youssef, Farid F.; Dookeeram, Karine; Basdeo, Vasant; Francis, Emmanuel; Doman, Mekaeel; Mamed, Danielle; Maloo, Stefan; Degannes, Joel; Dobo, Linda. "Stress alters personal moral decision making". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 37 (4): 491–498. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.07.017.

- Jump up ^ Valdesolo, Piercarlo; DeSteno, David (2006-06-01). "Manipulations of Emotional Context Shape Moral Judgment". Psychological Science. 17 (6): 476–477. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 16771796. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01731.x.

- Jump up ^ Ciaramelli, Elisa; Muccioli, Michela; Làdavas, Elisabetta; Pellegrino, Giuseppe di (2007-06-01). "Selective deficit in personal moral judgment following damage to ventromedial prefrontal cortex". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2 (2): 84–92. ISSN 1749-5024. PMC 2555449

. PMID 18985127. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm001.

. PMID 18985127. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm001. - Jump up ^ Navarrete, C. David; McDonald, Melissa M.; Mott, Michael L.; Asher, Benjamin (2012-04-01). "Virtual morality: Emotion and action in a simulated three-dimensional "trolley problem".". Emotion. 12 (2): 364–370. ISSN 1931-1516. doi:10.1037/a0025561.

- Jump up ^ Crockett, Molly J.; Clark, Luke; Hauser, Marc D.; Robbins, Trevor W. (2010-10-05). "Serotonin selectively influences moral judgment and behavior through effects on harm aversion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (40): 17433–17438. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2951447

. PMID 20876101. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009396107.

. PMID 20876101. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009396107. - Jump up ^ Bernhard, Regan M.; Chaponis, Jonathan; Siburian, Richie; Gallagher, Patience; Ransohoff, Katherine; Wikler, Daniel; Perlis, Roy H.; Greene, Joshua D. (2016-12-01). "Variation in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is associated with differences in moral judgment". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 11 (12): nsw103. ISSN 1749-5016. PMC 5141955

. PMID 27497314. doi:10.1093/scan/nsw103.

. PMID 27497314. doi:10.1093/scan/nsw103. - Jump up ^ "'Trolley Problem': Virtual-Reality Test for Moral Dilemma – TIME.com". TIME.com.

- Jump up ^ Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology – ISSN 1933-5377 – volume 4(3). 2010

- Jump up ^ Bourget, David; Chalmers, David J. (2013). "What do Philosophers believe?". Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Jump up ^ Patrick Lin (October 8, 2013). "The Ethics of Autonomous Cars". The Atlantic.

- Jump up ^ Tim Worstall (2014-06-18). "When Should Your Driverless Car From Google Be Allowed To Kill You?". Forbes.

- Jump up ^ Jean-François Bonnefon; Azim Shariff; Iyad Rahwan (2015-10-13). "Autonomous Vehicles Need Experimental Ethics: Are We Ready for Utilitarian Cars?". Science. 352: 1573–1576. arXiv:1510.03346

. doi:10.1126/science.aaf2654.

. doi:10.1126/science.aaf2654. - Jump up ^ Emerging Technology From the arXiv (October 22, 2015). "Why Self-Driving Cars Must Be Programmed to Kill". MIT Technology review.

- Jump up ^ Bonnefon, Jean-François; Shariff, Azim; Rahwan, Iyad (2016). "The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles". Science. 352 (6293): 1573–1576. PMID 27339987. doi:10.1126/science.aaf2654.

- Jump up ^ "Moral Machine".

- Jump up ^ Sütfeld, Leon R.; Gast, Richard; König, Peter; Pipa, Gordon. "Using Virtual Reality to Assess Ethical Decisions in Road Traffic Scenarios: Applicability of Value-of-Life-Based Models and Influences of Time Pressure". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 11. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00122.

- Jump up ^ Skulmowski, Alexander; Bunge, Andreas; Kaspar, Kai; Pipa, Gordon (December 16, 2014). "Forced-choice decision-making in modified trolley dilemma situations: a virtual reality and eye tracking study". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 8. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00426.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barbara Mikkelson (27 February 2010). "The Drawbridge Keeper". Snopes.com. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Jump up ^ lewis-8 (25 January 2003). "Most (2003)". IMDb.

- Jump up ^ David Cole (March 10, 2016). "Killing from the Conference Room". The New York Review of Books.

- Jump up ^ "The Trolley Problem". Know Your Meme. 2017.

- Jump up ^ Feldman, Brian (9 August 2016). "The Trolley Problem Is the Internet’s Most Philosophical Meme". 2017, New York Media LLC. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- Jump up ^ Raicu, Irina (8 June 2016). "Modern variations on the 'Trolley Problem' meme". Vox Media, Inc. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- Jump up ^ Zhang, Linch (1 June 2016). "Behind the Absurd Popularity of Trolley Problem Memes". TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

External links[edit]

This audio file was created from a revision of the article "Trolley problem" dated 2012-04-30, and does not reflect subsequent edits to the article. (Audio help)

- Should You Kill the Fat Man?

- Forced-choice decision-making in modified trolley dilemma situations: a virtual reality and eye tracking study

- Can Bad Men Make Good Brains Do Bad Things?

- The Trolley Problem as a retro video game

- Trolley Problem – Killing and Letting Die

- The Trolley Problem is Fundamentally Flawed

No comments:

Post a Comment