Something like the Universal Debating Project needs to be fully implemented in order to counteract false news, and misinformation, and indeed, disinformation.

Blogger Ref http://www.p2pfoundation.net/Universal_Debating_Project

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the type of hoax. For its impact and the websites that publish it, see Fake news website. For other uses, see Fake news (disambiguation).

| It has been suggested that this article be merged into Fake news website. (Discuss) Proposed since January 2017. |

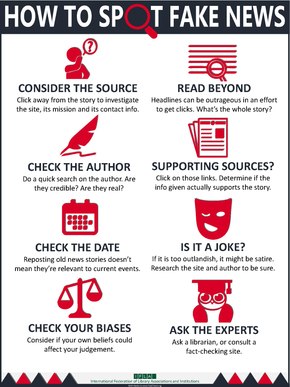

"How To Spot Fake News", an infographic published by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

| This article is part of a series on |

| Misinformation and disinformation |

|---|

|

| Journalism |

|---|

|

| Areas |

| Genres |

| Social impact |

| News media |

| Roles |

Contents

[hide]Definition[edit]

Fake news has been defined as news which is "completely made up and designed to deceive readers to maximize traffic and profit".[4] News satire uses exaggeration and introduces non-factural elements, but is intended to amuse or make a point, not deceive. Propaganda can also be fake news.[4]Identifying[edit]

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) published a summary in diagram form to assist people to recognise fake news.[5] Its main points are:- Consider the source (to understand its mission and purpose)

- Read beyond the headline (to understand the whole story)

- Check the authors (to see if they are real and credible)

- Assess the supporting sources (to ensure they support the claims)

- Check the date of publication (to see if the story is relevant and up to date)

- Ask if it is a joke (to determine if it is meant to be satire)

- Review your own biases (to see if they are affecting your judgement)

- Ask experts (to get confirmation from independent people with knowledge).

Historical examples[edit]

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2017) |

Ancient and medieval[edit]

Significant fake news stories can be traced back to the forged 8th century Donation of Constantine,[6] and Octavian's 1st century campaign of misinformation against Mark Antony.[7]Nineteenth century[edit]

One of the earliest instances of fake news was the Great Moon Hoax of 1835. The New York Sun published articles about a real-life astronomer and a made-up colleague who, according to the hoax, had observed bizarre life on the moon. The fictionalized articles successfully attracted new subscribers, and the penny paper suffered very little backlash after it admitted the series had been a hoax the next month.[8][7]Twentieth century[edit]

Fake news is similar to the concept of yellow journalism and political propaganda, frequently employing the same strategies used by early 20th century penny presses.[9][10][11] In the late 1800s, Joseph Pulitzer and other yellow press publishers goaded the United States into the Spanish–American War, which was precipitated when the U.S.S. Maine exploded in the harbor of Havana, Cuba.[12]The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has published that, through its reporter Walter Duranty, The New York Times printed "fake news" "depicting Russia as a socialist paradise."[13] During 1932–1933, The New York Times published numerous articles by its Moscow bureau chief, Walter Duranty, denying that the Soviet Union at that time starved to death between 2.4[14] and 7.5[15] million of its own citizens, a genocide now known as the Holodomor.[16] The New York Times now claims this was "some" of "its worst" reporting.[17] This years-long fake news episode has been noted by multiple pundits in Australia,[18] the U.S.,[19] and the UK.[20]

After Hitler and the Nazi party rose to power in Germany in 1933, they established the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under the control of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.[21] The Nazis used both print and broadcast journalism to promote their agendas, either by obtaining ownership of those media or exerting political influence.[22] Throughout World War II, both the Axis and the Allies employed fake news in the form of propaganda to persuade publics at home and in enemy countries.[23][24] The British Political Warfare Executive used radio broadcasts and distributed leaflets to discourage German troops.[21]

Twenty-first century[edit]

In the 21st century, the use and impact of fake news became widespread, as well as the usage of the term. Besides being used to refer to made-up stories designed to deceive readers to maximize traffic and profit, the term was also used to refer to satirical news, whose purpose is not to mislead but rather to inform viewers and share humorous commentary about real news and the mainstream media.[25][26] American examples of satire (as opposed to fake news) include the television show Saturday Night Live's Weekend Update, The Daily Show, The Colbert Report and The Onion newspaper.[27][28] [29]Russia used "dezinformatsiya" (дезинформация) or disinformation in 2014 to create a counter narrative after Russian-backed Ukrainian rebels shot down Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 using a Russia-supplied missile. False news stories often originated with Russia's state-sponsored television news, RT.[30] In 2016, NATO claimed it had seen a significant rise in Russian propaganda and fake news stories since the invasion of Crimea in 2014.[31] Fake news stories originated from the Russian government officials were also circulated internationally by Reuters news agency and published in the most popular news websites in the United States.[32]

In the United States during the 2016 election campaign for the 45th President, fake news was particularly prevalent, although a working paper by researchers at Stanford University and New York University concluded that fake news had "little to no effect" on its outcome, noting that only 8 percent of voters read a fake news story and that recall of the stories was low.[33][34] Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel became a target for fake news in the run-up to the 2017 German federal election following the election of U.S. President Donald Trump.[35]

In the early weeks of his presidency, U.S. President Donald Trump frequently used the term "fake news" to refer to traditional news media, creating confusion about its meaning.[36] After Republican Colorado State Senator Ray Scott used the term as a reference to a column in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, the newspaper's publisher threatened a defamation lawsuit.[37][38]

Impact[edit]

Main article: Fake news by country

The impact of fake news is global and part of a worldwide phenomenon.[39] The capacity of fake news to mislead would always lead to impaired judgements about truth and consequently ill-informed judgements about what actions and policies are appropriate. Fake news is spread through social media and also often through the use of fake news websites, which, in order to gain credibility, specialize in inventing attention-grabbing news, often impersonating well-known news sources.[40][41][42] Fake news has been used in email phishing attacks for many years, with sensationalist fabrications providing incentive for users to click links and have their computers infected with malware.[43]The controversy over fake news has been described as both a moral panic and mass hysteria from commentators on both sides of the American political aisle, including Glenn Greenwald, Ed Morrissey,and Jack Shafer.[44][45][46][47][48][49][50]

Involvement of social media[edit]

In the 21st century, the capacity to mislead was enhanced by the widespread use of social media. For example, one 21st century that enabled fake news' proliferation was the Facebook newsfeed.[51][52] In late 2016 fake news gained notoriety following the uptick in news content by this means,[53][2] and its prevalence on the micro-blogging site Twitter.[53]In the United States, a large portion of Americans use Facebook or Twitter to receive news.[54] This, in combination with increased political polarization and filter bubbles, led to a tendency for readers to mainly read headlines. Fake news was implicated in influencing the 2016 American presidential election.[55][56] Fake news saw higher sharing on Facebook than legitimate news stories,[57][58][59] which analysts explained was because fake news often panders to expectations or is otherwise more exciting than legitimate news.[58][11] Facebook itself initially denied this characterization.[60][52] A Pew Research poll conducted in December 2016 found that 64% of U.S. adults believed completely made-up news had caused "a great deal of confusion" about the basic facts of current events, while 24% claimed it had caused "some confusion" and 11% said it had caused "not much or no confusion".[61] Additionally, 23% of those polled admitted they had personally shared fake news, whether knowingly or not.

Research from Northwestern University concluded that 30% of all fake news traffic, as opposed to only 8% of real news traffic, could be linked back to Facebook.[62] Fake news consumers, they concluded, do not exist in a filter bubble; many of them also consume real news from established news sources.[62] The fake news audience is only 10 percent of the real news audience, and most fake news consumers spent a relatively similar amount of time on fake news compared with real news consumers—with the exception of Drudge Report readers, who spent more than 11 times longer reading the website than other users.[62]

After the 2016 American election and the run-up to the German election, Facebook began labeling and warning of inaccurate news[63][64][65] and partnered with independent fact-checkers to label inaccurate news, warning readers before sharing it.[63][64][66]

In China, fake news items have occasionally spread from such sites to more well-established news-sites resulting in scandals including "Pizzagate".[67] In the wake of western events, China's Ren Xianling of the Cyberspace Administration of China suggested a "reward and punish" system be implemented to avoid fake news.[68]

See also[edit]

- Alternative news

- Black propaganda

- Fallacy of false attribution

- False flag

- Information warfare

- Internet meme

- Lying press - German phrase

- Memetics

- Politico-media complex

- Samizdat

- Underground Press

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hunt, Elle (December 17, 2016). "What is fake news? How to spot it and what you can do to stop it". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Woolf, Nicky (November 11, 2016). "How to solve Facebook's fake news problem: experts pitch their ideas". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ Callan, Paul. "Sue over fake news? Not so fast". CNN. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hunt, Elle (December 17, 2016). "What is fake news? How to spot it and what you can do to stop it". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "How to Spot Fake News". IFLA blogs. 27 January 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Jump up ^ "Before Jon Stewart". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Long and Brutal History of Fake News". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "The Great Moon Hoax - Aug 25, 1835 - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "To Fix Fake News, Look To Yellow Journalism | JSTOR Daily". JSTOR Daily. November 29, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "Russian propaganda effort helped spread 'fake news' during election, experts say". Washington Post. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Agrawal, Nina. "Where fake news came from — and why some readers believe it". latimes.com. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "Milestones: 1866–1898 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "Judy Asks: Can Fake News Be Beaten?". Carnegie Europe. 25 January 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

Stalin fed fake news to New York Times correspondent Walter Duranty, who won a Pulitzer Prize for depicting Russia as a socialist paradise.

- Jump up ^ David R. Marples. Heroes and Villains: Creating National History in Contemporary Ukraine. p.50

- Jump up ^ "International Recognition of the Holodomor". Holodomor Education. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- Jump up ^ Meyer, Karl E. (June 24, 1990). "The Editorial Notebook; Trenchcoats, Then and Now". New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "Subscribe | theaustralian". www.theaustralian.com.au. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "Behind the Headlines: Fake News". ABC 7 - KATV. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

But what exactly is fake news? How about New York Times Moscow Bureau Chief Walter Duranty? His false reports covered-up the genocide of millions of Ukrainians by the Soviet Union in the 1930s.

- Jump up ^ Beckett, Lois (November 27, 2016). "Fidel Castro's fake news: did claim he tricked the New York Times dupe us all?" – via The Guardian.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "American Experience . The Man Behind Hitler . | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "The Press in the Third Reich".

- Jump up ^ Wortman, Marc (2017-01-29). "The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. into World War II". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "Inside America's Shocking WWII Propaganda Machine". 2016-12-19. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ JEREMY W. PETERS (25 December 2016). "Wielding Claims of 'Fake News,' Conservatives Take Aim at Mainstream Media". The New York Times.

- Jump up ^ http://www.cbsnews.com/news/daily-show-with-jon-stewart-last-show-influence-on-media-politics/

- Jump up ^ "Why SNL's 'Weekend Update' Change Is Brilliant". Esquire. 2014-09-12. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "Area Man Realizes He's Been Reading Fake News For 25 Years". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "'The Daily Show (The Book)' is a reminder of when fake news was funny". newsobserver. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ Macfarquhar, Neil (2016-08-28). "A Powerful Russian Weapon: The Spread of False Stories". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "NATO says it sees sharp rise in Russian disinformation since Crimea seizure". Reuters. 2017-02-11. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ Watanabe, Kohei (2017-02-08). "The spread of the Kremlin's narratives by a western news agency during the Ukraine crisis". The Journal of International Communication. 0 (0): 1–21. doi:10.1080/13216597.2017.1287750. ISSN 1321-6597.

- Jump up ^ Christopher Ingraham (24 January 2017). "Real research suggests we should stop freaking out over fake news". The Washington Post.

- Jump up ^ Crawford, Krysten. "Stanford study examines fake news and the 2016 presidential election". Stanford News. Stanford University. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "Angela Merkel replaces Hillary Clinton as prime target of fake news, analysis finds". Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "With 'Fake News,' Trump Moves From Alternative Facts To Alternative Language". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ Post, The Washington. "Grand Junction Daily Sentinel standing up to state lawmaker's charges of "fake news" – The Denver Post". Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ "When A Politician Says 'Fake News' And A Newspaper Threatens To Sue Back". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Jump up ^ Connolly, Kate; Chrisafis, Angelique; McPherson, Poppy; Kirchgaessner, Stephanie; Haas, Benjamin; Phillips, Dominic; Hunt, Elle; Safi, Michael (December 2, 2016). "Fake news: an insidious trend that's fast becoming a global problem". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- Jump up ^ Chen, Adrian (June 2, 2015). "The Agency". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Jump up ^ LaCapria, Kim (November 2, 2016), "Snopes' Field Guide to Fake News Sites and Hoax Purveyors - Snopes.com's updated guide to the internet's clickbaiting, news-faking, social media exploiting dark side.", Snopes.com, retrieved November 19, 2016

- Jump up ^ Ben Gilbert (November 15, 2016), "Fed up with fake news, Facebook users are solving the problem with a simple list", Business Insider, retrieved November 16, 2016,

Some of these sites are intended to look like real publications (there are false versions of major outlets like ABC and MSNBC) but share only fake news; others are straight-up propaganda created by foreign nations (Russia and Macedonia, among others).

- Jump up ^ Tomlinson, Kerry (27 January 2017). "Fake news can poison your computer as well as your mind". Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Jump up ^ Morozov, Evgeny (7 January 2017). "Moral panic over fake news hides the real enemy – the digital giants". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Jump up ^ Shafer, Jack (22 November 2016). "The Cure for Fake News Is Worse Than the Disease". Politico. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Jump up ^ Gobry, Pascal-Emmanuel (12 December 2016). "The crushing anxiety behind the media's fake news hysteria". The Week. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Jump up ^ Bottum, Joseph. "There's Nothing New About Fake News". The Washington Free Beacon. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Jump up ^ Majors, Bruce. "'Fake News' Hysteria is about profit". The Daily Caller. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Jump up ^ Greenwald, Glenn. "Russia Hysteria Infects WashPost Again: False Story About Hacking US Electrical Grid". The Intercept. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Jump up ^ Morrissey, Edward. "The Snarling Contempt of the Media's Fake News Hysteria". RealClearPolitics. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Jump up ^ Isaac, Mike (December 12, 2016). "Facebook, in Cross Hairs After Election, Is Said to Question Its Influence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Matthew Garrahan and Tim Bradshaw, Richard Waters, (November 21, 2016). "Harsh truths about fake news for Facebook, Google and Twitter". Financial Times. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Long and Brutal History of Fake News". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ Gottfried, Jeffrey; Shearer, Elisa (May 26, 2016). "News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2016". Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "Forget Facebook and Google, burst your own filter bubble". Digital Trends. December 6, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ Solon, Olivia (November 10, 2016). "Facebook's failure: did fake news and polarized politics get Trump elected?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "This Analysis Shows How Fake Election News Stories Outperformed Real News On Facebook". BuzzFeed. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Just how partisan is Facebook's fake news? We tested it". PCWorld. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "Fake news is dominating Facebook". 6abc Philadelphia. 2016-11-23. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ Isaac, Mike (November 12, 2016). "Facebook, in Cross Hairs After Election, Is Said to Question Its Influence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ Barthel, Michael; Mitchell, Amy; Holcomb, Jesse (2016-12-15). "Many Americans Believe Fake News Is Sowing Confusion". Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Is 'fake news' a fake problem?". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stelter, Brian (January 15, 2017). "Facebook to begin warning users of fake news before German election". CNNMoney. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Clamping down on viral fake news, Facebook partners with sites like Snopes and adds new user reporting". Nieman Lab. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- Jump up ^ Kuchler, Hannah (January 15, 2017). "Facebook rolls out fake-news filtering service to Germany". Financial Times. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- Jump up ^ Kuchler, Hannah (January 15, 2017). "Facebook rolls out fake-news filtering service to Germany". Financial Times. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "Evidence ridiculously thin for Clinton sex network claim". @politifact. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Jump up ^ "China says terrorism, fake news impel greater global internet curbs". Reuters. November 20, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

No comments:

Post a Comment